Hart’s full team includes fellow electrical engineering students Thomas Shanahan, of Haverhill, Mass.; Nathaniel DeParis, of Methuen, Mass.; and Abdul Alabodi, of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; mechanical engineering students Paul Gorton, of Shelton, Conn. and Mike Stehnach, of Little Falls, N.Y.; and computer science engineering student Andrew Joyola, of Methuen.

The faculty advisor is associate professor William Bowhers of electrical and computer engineering.

“My goal is to put Merrimack engineering on the map, so to say,” said Hart, of Rockland, Mass. “If we can go in there and be competitive with the other schools selected it would be really cool.”

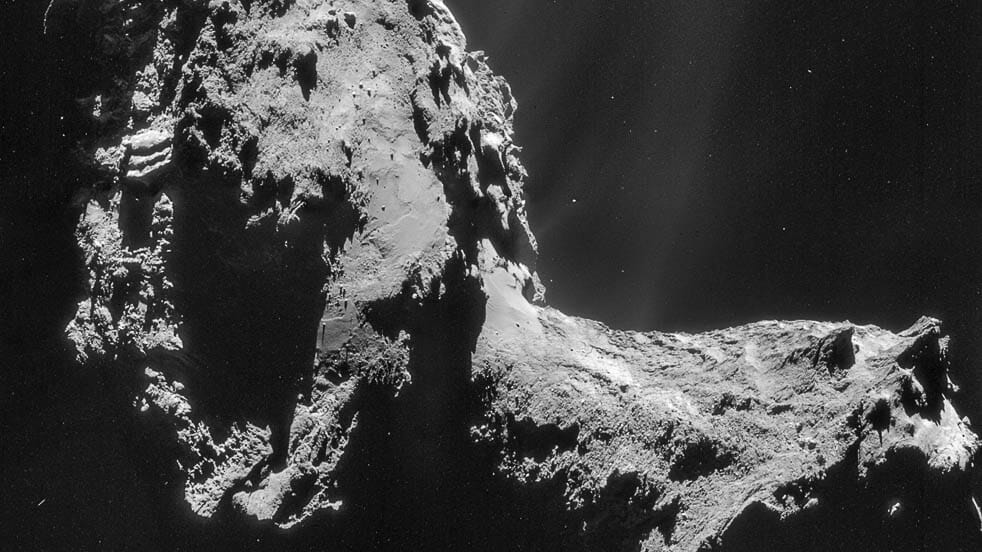

The 50 teams must guide robots through an arena of Mars-like terrain to gather 22 pounds of regolith in 10 minutes. Regolith is material such as dust, soil and broken rock that covers solid rock on Earth and its moon, Mars, asteroids, and other planets and moons.

According to NASA’s web page, the project has other-world implications for developing its plans to visit Mars as early as the 2030s.

“The technology concepts developed by the university teams for this competition conceivably could be used to robotically mine regolith resources on Mars,” according to the web page. “NASA will directly benefit from the competition by encouraging the development of innovative robotic excavation concepts from universities which may result in clever ideas and solutions which could be applied to an actual excavation device or payload.”

The physical properties of basaltic regolith and Mars’ atmosphere, which is just three-eighths that of Earth’s, make excavation technically challenging, the web page said.

Hart was researching engineering competitions when he found the NASA challenge. As part of the requirements he needed a faculty member to write a letter of support and Bowhers was an enthusiastic supporter, Hart said.

Then he went to work assembling his crew. He knew Shanahan and DeParis from class. Gorton and Stehnach volunteered and Joyola was recommended by a mutual friend.

The competition is an educational venue that can help professionally, Stehnach said.

“We’re trying to learn about as many fields of engineering as possible,” he said.

Unlike robotics competitions for high schoolers, NASA doesn’t supply a box of robotics parts for its mining robotics competition.

Merrimack’s team has to build a robot no longer than 1.5 meters, no wider than .75 meter and no higher than 1.5 meters.

The competition includes what Hart called a “huge engineering project paper.” The paper will detail the team works developing the robot, the materials it used and how it accomplished its goals.

The team has put together a draft drawing of the robot showing wheels, and conveyor belts to move the regolith. A team member will drive the robot and operate the conveyor belts using joysticks from the remote control.

The detailed engineering and construction will start during the spring semester.

“As a faculty program manager, I’m always worried concerned about the time,” Bowhers said. “So much to do and so little time.”

The threat of being embarrassed on a national stage is enough to keep the team motivated.

“It’s like do-or-die, we’d better get it done,” Hart said. “It’s a fun project but the fact is, it’s for NASA and that’s incentive enough.

The mechanical engineers will build the framework, including the wheels and conveyor belts. The electrical engineers will ensure it can move.

“Our job is to make sure the robot can moved forward and backward, side-to-side remotely,” Hart said. “Also, we need to make sure both conveyor belts can move up and down. Our toughest challenge as electrical engineers is the remote.”

As part of NASA’s requirements, students must earn at least one credit for taking part in the team. Merrimack is offering two credits but the competition also counts as the capstone project for the electrical engineering students.

Scoring for the competition will include the engineering paper the team must write, dust proofing the robot, and ability for the bot to collect materials, Hart said.

Hart is looking forward to the NASA requirement that the team perform outreach to an area school to explain the project and how they are building the robot with a question-and-answer session.

There are many unknowns surrounding the team, including how it’ll get to Florida just three days after graduation, Bowhers said. Even so, check-in for the competition at Kennedy Space Center is May 18, the day after graduation.

“Donations are welcome,” Stehnach quipped.